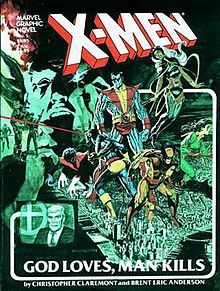

X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills

| X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills | |

|---|---|

| |

| Date | 1982 |

| Main characters | X-Men Magneto William Stryker |

| Series | Marvel Graphic Novel |

| Publisher | Marvel Comics |

| Creative team | |

| Writers | Christopher Claremont |

| Artists | Brent Eric Anderson |

| Colourists | Steve Oliff |

| ISBN | 0-7851-0039-3 |

X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills is a graphic novel published by Marvel Comics in 1982. It was written by Christopher Claremont and illustrated by Brent Eric Anderson, and it was released as the fifth entry in the Marvel Graphic Novel series. It stars the superhero team the X-Men in a battle against William Stryker, a televangelist who seeks to eradicate super-powered mutants like the X-Men. Claremont wrote God Loves, Man Kills to be accessible as a stand-alone story that conveys the themes behind the X-Men in a more mature tone. The story was written at the height of televangelism and takes a critical approach to the practice, presenting Stryker as an example for the danger of its abuse. It examines the nature of discrimination, using mutants as an allegory for persecuted groups while invoking racial discrimination and antisemitism. God Loves, Man Kills received critical praise and become one of the most popular stories featuring the X-Men. Critics highlighted its tone and thematic elements, while retrospective reviews have described its long-term relevance to societal issues. It was followed by a sequel in X-Treme X-Men #25–30 (2003) and was adapted into the film X2: X-Men United (2003).

In God Loves, Man Kills, Stryker leads an ideological movement describing mutants as ungodly while he has his Purifiers hunt and kill them. After the Purifiers take some of the X-Men captive, the remaining members work with their nemesis Magneto to save them. Stryker brainwashes the leader of the X-Men, Professor Xavier, and harnesses his telepathic powers to launch psychic attacks against all the world's mutants during a televised sermon. The X-Men free Xavier and give their own speech to refute Stryker's beliefs. Stryker draws a gun to shoot the X-Men, but a police officer shoots him first. Although Stryker is defeated, Magneto warns the X-Men that Stryker's ideas are not and that the X-Men's ideal of peaceful coexistence will fail.

Creation and publication

[edit]X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills was written by Chris Claremont and drawn by Brent Anderson.[1] Claremont had been the writer for Uncanny X-Men since 1975, and his contributions to the series made it into one of the major franchises of Marvel Comics.[2] By the time of God Loves, Man Kills, Claremont had already written two franchise-defining X-Men stories: "The Dark Phoenix Saga" (1980) and "Days of Future Past" (1981).[3] Steve Oliff was the book's colorist and Tom Orzechowski lettered it. Relative to Marvel's other comic books of the time, Oliff used muted colors.[4]

Anderson was chosen by Claremont and editor Louise Simonson following the departure of their original artist, Neal Adams. Anderson had drawn X-Men comics before but had not worked extensively on the series.[5] Anderson uses a more abstract art style relative to other comic book artists. When drawing fight scenes in God Loves, Man Kills, he frequently shifts away from long shots to focus on one or two specific characters as they act. He arranges the panels on a page depending on the scene, creating an effect where a calm, serious scene has the panels arranged symmetrically while a more chaotic scene moves quickly through several panels.[6] He modeled the character of William Stryker after then-Secretary of State Alexander Haig.[7]

God Loves, Man Kills was published in 1982 as the fifth entry of the Marvel Graphic Novel series.[8] It was presented as a standalone story, separate from the main Uncanny X-Men comic book series. The series was following a story set in space at the time, while God Loves, Man Kills told a more grounded story.[9] It was not intended to take place in the same continuity as the main series.[2] Claremont wrote God Loves, Man Kills with the intention that it would be accessible to audiences who were not familiar with the X-Men and convey the franchise's themes. It was the first graphic novel about the X-Men, and the second about the franchise's mutants after The New Mutants.[7]

It was the hope of those at Marvel Comics that the story's handling of more serious themes would prove the advantages of a longer graphic novel style publication.[3] God Loves, Man Kills cost $5.95 (equivalent to $18.79 in 2023) on its release, compared to the typical $0.60 (equivalent to $1.89 in 2023) charged for issues of the comic book series. To reflect the more formal publication of the book, it is divided into chapters and Claremont was credited as Christopher rather than his usual credit of Chris.[9]

Plot summary

[edit]In the prologue, two children are chased and killed by a group called the Purifiers. The Purifiers hang their bodies from a swingset with a label reading "Mutie", but Magneto lays their bodies to rest before they are found by other children. In his office, televangelist William Stryker reads from the Bible and goes over his information on the X-Men and their mutant powers: Cyclops, Storm, Wolverine, Colossus, Kitty Pryde, Nightcrawler, and their leader Professor Xavier.

Chapter one begins with Kitty fighting a boy who supports Stryker's anti-mutant crusade before the Colossus stops her from hurting the boy. Their teacher Stevie Hunter tells Kitty to ignore the boy's discrimination, causing Kitty to lash out. At the X-Mansion they watch a televised debate between Stryker and Xavier. Stryker appears to win the debate, so the X-Men practice combat training in the Danger Room to distract themselves. On the way home from the debate, Xavier, Storm, and Cyclops are ambushed by Purifiers and appear to be killed.

Chapter two has Kitty Pryde and her friend Ilyana Rasputin mourn the dead X-Men until they find a spying device on the X-Mansion grounds and wait to see who left it. Wolverine and Colossus investigate the car crash where the other X-Men were killed, and Wolverine determines it must be staged. They discover they are being watched by Purifiers and engage in combat. Their nemesis Magneto arrives to help, and they take the Purifiers captive. Other Purifiers arrive at the X-Mansion and capture Kitty and Ilyana. Magneto tortures the captive Purifiers for information to the dismay of Colossus and Nightcrawler. A Purifier admits they work for Stryker.

Stryker tortures Xavier in chapter three, controlling Xavier's mind so he thinks that he is being crucified by demonic versions of the X-Men. Stryker explains why he hates mutants, saying that he killed his newborn child upon discovering it was a mutant and that he realized he was chosen by God to eradicate mutants. Kitty escapes from the Purifiers and leads them on a chase before Magneto and the X-Men arrive to save her. At Stryker's headquarters, Xavier is brainwashed and appears to kill Cyclops and Storm on Stryker's orders. The X-Men infiltrate the building and defeat Anne, and they discover that Xavier had only pretended to kill them by lowering their vitals.

Stryker's televised sermon at Madison Square Garden takes place in chapter four. He rigs Xavier to a Cerebro machine that will amplify his telepathic powers so he can target and kill all mutants with his mind. Magneto flies into the arena and confronts Stryker, who directs Xavier's telepathic attack at Magneto and then all other mutants. Anne realizes she is a mutant when she is affected, so Stryker kills her. The X-Men free Xavier from the machine and give their own speech at the pulpit challenging Stryker's ideas. Stryker draws a gun to shoot Kitty, but a police officer working security shoots Stryker first.

Magneto confronts the X-Men in the epilogue, telling them that Stryker won because his ideas were still popular. Xavier considers joining Magneto's mutant separatist movement and is then ashamed of himself for contemplating the idea. Cyclops reminds him that flaws are what make him human.

Themes and analysis

[edit]Religious extremism

[edit]

The predominant message of God Loves, Man Kills is the moral responsibility of opposing religious extremism.[10] The book was created when televangelism was at the height of its popularity.[11] Claremont based Stryker on the Christian right, lampooning figures such as Jerry Falwell and his Moral Majority movement.[6] Stryker is explicitly defined as a televangelist as opposed to any other form of religious leader,[12] and he is used to criticize the practice as a dangerous force that can be abused.[11] When Professor Xavier is almost swayed to Magneto's point of view that mutants must use violent methods to fight humanity, Cyclops reminds him that being flawed is part of being human, challenging the air of infallibility implied by televangelists.[13]

The story suggests that national political figures, including the president, are interested in Stryker's message, reflecting concerns among critics of televangelism that it would influence political trends.[14] Cyclops worries that Stryker's appeal to fear is stronger than Professor Xavier's appeal to ideals.[15] Conversely, it indicates that many people are concerned about the nature of Stryker's message, including other evangelical leaders.[16] While Stryker participates in a televised debate, two studio operators express concern about how Stryker's personability on television lets him spread dangerous ideas.[15] Other religious leaders are described as rejecting Stryker's message after his hypocrisy is exposed at the end of the story, suggesting that his violent approach is not inherent to religious movements.[17] By the end of the 1980s, many prominent televangelists faced backlash similar to Stryker as scandalous information about them and allegations of hypocrisy became public.[11]

Stryker's character and the nature of the conflict are established in the second scene as Stryker reads Deuteronomy 17:2–5 from the Bible. This passage commands the killing of those who worship other gods, suggesting a motive for the lynching that will recur through the plot.[12] Stryker continues citing passages from the Bible throughout the story to support his views. These include Matthew 10:34–35 and 37, Ecclesiastes 12:13, Isaiah 1:14, and Ezekiel 18:20. He cites Genesis 1:1, Genesis 1:27, and Genesis 2:7 in his sermon at Madison Square Garden to challenge the theory of evolution and argue that mutants are ungodly.[18] When he is attacked by Magneto, he recites Revelation 13:11, Revelation 13:15, Revelation 20:9–10, Ecclesiastes 12:13, Leviticus 26:24, Isaiah 1:4, and Ezekiel 18:4.[19]

The method Stryker uses to brainwash Professor Xavier is explicitly biblical, as he is forced to believe that his students are demonic beings and that they are crucifying him.[20] The X-Men do not invoke religious imagery back to Stryker as they confront him. Instead, Cyclops questions why Stryker should be the authority on God's will and suggests that mutants may be normal humans while non-mutants are the deviations. When Stryker points to Nightcrawler as an example of a non-human, Kitty Pryde says that her care for Nightcrawler outweighs any beliefs about God that Stryker professes.[19]

Discrimination

[edit]By the time of the book's publication, themes relating to racial discrimination had already long been prevalent in Uncanny X-Men.[2] God Loves, Man Kills took a more serious tone compared to its comic book counterpart, addressing social issues more directly.[9] God Loves, Man Kills was published shortly after The Uncanny X-Men #150 (1981), which revealed that Magneto was a Holocaust survivor, and his presence in the story allows for comparisons to the Holocaust to be made. Magneto describes his experience when Cyclops accuses him of wanting a mutant-led dictatorship. Kitty Pryde is also Jewish, and her Star of David necklace is visible when she is arguing with one of Stryker's supporters.[21] God Loves, Man Kills is likewise more profane than typical publications of Marvel Comics: Wolverine uses the word bastard as a derogatory term and Kitty Pryde mentions the word nigger while discussing hate speech.[22] Claremont and Anderson felt that the latter was an appropriate way for the character to make her point after being told to tolerate discrimination.[7]

Stryker's rejection of the theory of evolution reflects contemporary fears that televangelism would promote anti-intellectualism.[23] His subsequent belief that mutants defy the creation of man in God's image is reminiscent of the Christian Identity movement, which holds similar views about race.[24] Stryker believes that mutants are created by Satan and that God has chosen him to eradicate the mutants.[25] By drawing his hatred of mutants from religion, he becomes a villain who believes in absolute truths and cannot be reasoned with.[26] Stryker creates a collective identity for his supporters by defining themselves as not mutants, and he defines mutants as a species separate from humanity and uses this to justify violence against them.[27] He defines Professor X as the symbol of this othered group by labeling him as the Antichrist, giving him further justification to destroy the mutants.[16] The opening scene of God Loves, Man Kills establishes the story's theme by depicting two children being lynched by people calling themselves Purifiers.[10] This establishes the extent to which Stryker and the Purifiers are willing to use violence,[28] and it demonstrates the success of Stryker's dehumanization of mutants in the minds of his supporters.[24] An element of irony is introduced when it is revealed that Stryker's own child was a mutant, suggesting that he is acting hypocritically in his crusade against mutants.[11]

Unlike most X-Men stories, the villain of God Loves, Man Kills is not a supervillain. Rather than represent ideas metaphorically as heroes fight villains, the story makes its message the main point of conflict.[10] This is foreshadowed in how it introduces the X-Men with Kitty Pryde fighting a man who expresses support for Stryker, which she acknowledges is different from fighting a supervillain. Professor Xavier describes the theme explicitly by contrasting their physical battles against Magneto with the ideological battle against Stryker. The X-Men are at a disadvantage, as their training has only prepared them for the former.[12] The characters must consider to what extent they are willing to compromise on their values to win. They join forces with Magneto, a mutant separatist who believes in the use of violence to achieve his ends.[3] Claremont presented Magneto as seeking vengeance, while the X-Men offered alternatives of mercy or justice.[7] Professor X nearly joins Magneto at the end of the story, suggesting he understands Magneto's beliefs.[3] Cyclops and Magneto both give speeches toward the end of the story indicating that they had not won because Stryker's ideas are still active even if his weapons were overcome.[29] The final message of God Loves, Man Kills is Cyclops expressing his belief that helping and caring for each other is the highest priority.[30]

Reception and legacy

[edit]Claremont later expressed his opinion that God Loves, Man Kills is the X-Men story that best represents the franchise and its purpose, and he recommended it above any other X-Men stories.[10] Alex Abad-Santos of Vox described it as the most important X-Men story.[7] Critics such as Jamie Hailstone of Den of Geek and Edward Haynes of Multiversity Comics praised God Loves, Man Kills in retrospective reviews for its complex themes and long-term relevance.[31][4] The book was criticized by televangelist Pat Robertson for its depiction of Professor Xavier being crucified, which he denounced as blasphemous on his program The 700 Club.[7]

God Loves, Man Kills was not acknowledged as part of the main Marvel Universe continuity in the years after its release.[32] A sequel was eventually published in X-Treme X-Men #25–30 (2003). In this story, Stryker escapes from prison and kidnaps Kitty Pryde to resume his crusade, using the same justifications to persecute mutants.[33] It builds on the theme by introducing the pastor Paul who uses similar evangelical beliefs to justify the persecution of humans.[34] A new story about Stryker's crusade, "Childhood's End", created by Craig Kyle and Christopher Yost, was published in New X-Men #20–27 (2006).[35] New editions of God Loves, Man Kills have been printed with new cover art, and a hardcover edition was published in 2007.[2] The book saw renewed attention in the 2010s as popular concerns about white supremacist movements grew, and Stryker was noted for his physical resemblance to then-Vice President Mike Pence.[7]

The film X2: X-Men United (2003) adapted many elements of God Loves, Man Kills.[36] The studio hired two screenwriters, David Hayter and Zak Penn, to write X2 and its sequel. Both wanted to use God Loves, Man Kills as source material. Hayter intended to combine God Loves, Man Kills with "The Phoenix Saga" so that Jean Grey was the threat that Stryker opposed. This aspect was eventually cut and "The Phoenix Saga" was only alluded to so it could be used later.[37] Like the graphic novel, X2 depicts the X-Men aligning with Magneto to fight Stryker after he kidnaps Professor Xavier. The film deviates from the graphic novel in several places.[36] Instead of a preacher, Stryker is a military scientist and is connected to Wolverine's origin.[38] Instead of killing his mutant child, Stryker has a living mutant son in the film.[36] The character Anne was replaced by the X-Men villain Lady Deathstrike to allow for a fight scene with Wolverine. Deathstrike's role was carried over to "God Loves, Man Kills II" where she is one of Stryker's followers.[39]

The direct analysis of real-world discrimination featured in God Loves, Man Kills became more common in the main Uncanny X-Men series over the following years.[9][3] Issues published in 1985 included a scene in which Professor Xavier is beaten in a hate crime and one in which rival pro-mutant and anti-mutant rallies form.[40] Similar themes carried over into spin-off series like Wolverine (1982) and The New Mutants (1983).[3] God Loves, Man Kills foreshadowed to depiction of Magneto as a sympathetic character whose argument of mutant solidarity might have merit.[4]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Davis 2012, p. 649.

- ^ a b c d Davis 2012, p. 648.

- ^ a b c d e f Davis 2012, p. 651.

- ^ a b c Haynes 2018.

- ^ Davis 2012, p. 649–650.

- ^ a b Davis 2012, p. 650.

- ^ a b c d e f g Abad-Santos 2017.

- ^ McLean 2008, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d Booy 2018, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d Rennaker 2014, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d Rennaker 2014, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Rennaker 2014, p. 80.

- ^ Rennaker 2014, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Rennaker 2014, p. 84.

- ^ a b Rennaker 2014, p. 81.

- ^ a b Clanton 2020, p. 58.

- ^ Rennaker 2014, p. 86.

- ^ Rennaker 2014, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Clanton 2020, p. 60.

- ^ Clanton 2020, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Rennaker 2014, p. 82.

- ^ Booy 2018, p. 95.

- ^ Rennaker 2014, p. 83.

- ^ a b Clanton 2020, p. 59.

- ^ Rennaker 2014, p. 85.

- ^ Clanton 2020, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Clanton 2020, p. 57.

- ^ Clanton 2020, p. 56.

- ^ Rennaker 2014, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Rennaker 2014, p. 88.

- ^ Hailstone 2008.

- ^ Booy 2018, p. 107.

- ^ Clanton 2020, p. 61.

- ^ Clanton 2020, p. 63.

- ^ Clanton 2020, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Davis 2012, p. 652.

- ^ McLean 2008, pp. 125–126.

- ^ McLean 2008, p. 126.

- ^ McLean 2008, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Booy 2018, pp. 94–95.

References

[edit]- Abad-Santos, Alex (May 3, 2017). "God Loves, Man Kills: the creators of the legendary X-Men story reflect on its 35-year legacy". Vox.

- Booy, Miles (2018). Marvel's Mutants: The X-Men Comics of Chris Claremont. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-83860-882-8.

- Clanton, Dan W. (2020). "'Because You Exist': Biblical Literature and Violence in the X-Men Comic Books". In Stevenson, Gregory (ed.). Theology and the Marvel Universe. Lexington Books. pp. 55–70. ISBN 978-1-9787-0615-6.

- Davis, Jim (2012). "X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills". In Beaty, Bart H.; Weiner, Stephen (eds.). Critical Survey of Graphic Novels: Heroes & Superheroes. Vol. 2. Salem Press. pp. 648–652. ISBN 978-1-58765-867-9.

- Hailstone, Jamie (August 11, 2008). "Revisiting The X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills". Den of Geek.

- Haynes, Edward (June 26, 2018). "X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills". Multiversity Comics.

- McLean, Thomas J. (2008). Mutant Cinema: The X-Men Trilogy from Comics to Screen. Sequart Research & Literacy Organization. ISBN 978-0-615-18690-0.

- Rennaker, Jacob (2014). "'Mutant hellspawn' or 'more human than you?' The X-Men Respond to Televangelism". In Darowski, Joseph J. (ed.). The Ages of the X-Men: Essays on the Children of the Atom in Changing Times. McFarland. pp. 77–90. ISBN 978-0-7864-7219-2.